The creation of the Australian industry and skills committee, and the governance and operational reform lessons of the new Australian curriculum development model

By: Simon Whatmore, Nicholas Wyman and Andrew Sezonov

Institute for Workplace Skills and Innovation, Victoria, Australia

Summary:

In 2015, the Commonwealth of Australia instituted new governance arrangements for curriculum development across its Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector. This paper outlines Council of Australian Governments (COAG) changes to the governance and operating model for validating nationally recognised training packages (the curriculum units taught through apprenticeship programs), leading to the establishment of the Australian Industry and Skills Committee (AISC).

This case study outlines the governmental reform process preceding the AISC’s formation, and reviews the impact of the AISC’s operational and validation model in the development, approval and implementation of new training packages in Australia.

Introduction

The vocational education sector is significant in advancing and innovating Australian education models. Described as “nationally directed, jurisdictionally implemented and industry-driven” (Atkinson and Stanwick, 2016), the sector is built around curriculum building blocks (training packages) – sets of nationally endorsed standards for recognising and assessing skills required by an individual to hold a vocation-specific qualification.

Since the late 1990s, Australian training packages were developed by Industry Skills Councils (ISCs). ISCs were independent, not-for-profit advisory bodies contracted by the Australian government to undertake package development as part of broader industry promotion and workforce development functions, which were then provided to a delegated ministerial committee for endorsement. This model ratified 60 training packages containing more than 1,600 qualifications covering 85 per cent of Australian occupations.

Established as bipartite federated stakeholder boards, each ISC functioned under its own unique constitution, board structure and funding system. Reflecting the VET sector’s origins in traditional trades training, these councils were technically oriented and incremental in the evolution of their training packages.

During the past decade, the suitability of the ISC training package development and endorsement model has been challenged by a number of macro trends, including: sectoral shifts in the economy and the expansion of service sector employment; the impact of technological change on traditional industrial processes; the dynamism and growth of jobs in ‘new economy’ sectors; and the deregulation and subsequent expansion of registered training organisations.

A survey of Australian employers identified concerns with the limitations of the ISCs’ siloed operating and development processes, indicating the need for structural change to develop and deliver training packages for an innovation-driven future focused on services, technology, cross-sector skills and flexible training delivery models (NCVER 2013). Industry’s reduced confidence in the relevancy and quality of the vocational training system, as well as declining apprenticeship enrolments at this time, led to the creation of the VET Reform Taskforce in November 2013.

The aim of this case study was to outline the reform process preceding AISC’s formation and review the impact its new governance model on the development and validation of new training packages in Australia, as assessed by key informants.

Methods and research design

The authors, who are active in the Australian vocational education sector, evaluated data from a range of public policy documents and submissions generated through the government’s consultation process before the AISC’s establishment (2014-2015).

The authors also obtained qualitative insight through conducting, in late 2018, a number of semi-structured key informant interviews, including representatives of the AISC, Australian government, training providers and industry stakeholder bodies to identify perceived benefits and drawbacks of the new governance model. A content analysis of these interview notes was undertaken to determine key themes for this conference presentation.

New governance model

In 2014, to help ensure the VET system could sufficiently respond to industry trends and generate training packages adequately supporting projected future skills needs, the ministerial-level COAG Industry and Skills Council (CISC) was formed.

At its inaugural meeting, the CISC agreed upon VET system reform objectives, particularly “to ensure that industry is involved in policy development and oversight of the performance of the VET sector and to streamline governance arrangements and committees” (COAG, 2014).

The council also initiated a thorough first-principle review of the sector, emphasising the key themes of: industry responsiveness; quality and regulation; funding and governance; and data and consumer information.

Designed to revitalise industry engagement with the national training system, the council conducted an extensive consultation process with the ISCs, relevant stakeholders and the public.

It then determined to reform the system through dissolution of the ISCs and the introduction of new governance arrangements in addition to the implementation of a contestability model and clear formal processes to access government funding for training package development.

The new model was designed to:

• strengthen industry leadership of training package development and review so that training better aligns with jobs in the modern economy

• prioritise the development and review of training packages based on industry demand for skills across sectors

• improve collaboration among stakeholders involved in training package development.

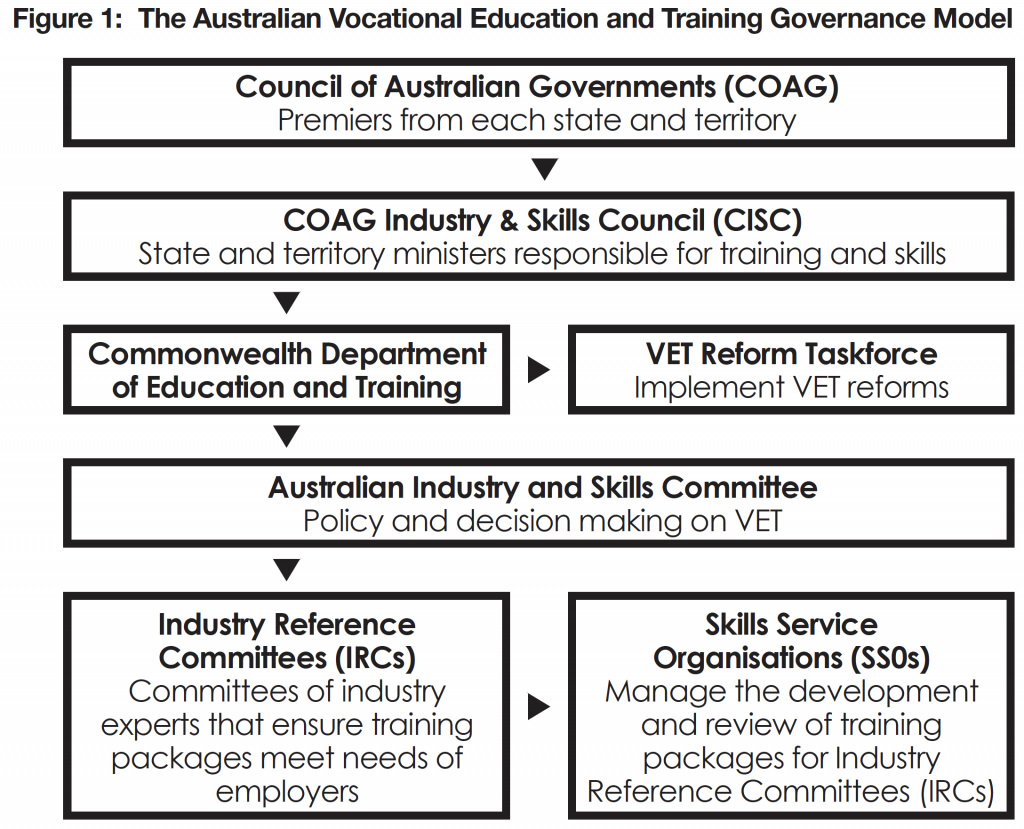

Under the new arrangements, the CISC distributed the tasks previously performed by the ISC across three new entities:

• Australian Industry and Skills Committee – a committee of industry leaders with the overarching formal responsibility for funding and approving training packages, advising the CISC on industry needs, and prioritising and managing the operations of the all IRCs and SSOs

• Industry Reference Committees (IRCs) – established by the AISC and populated by people with industry experience, skills and knowledge, IRCs provide expert advice, ensuring training packages meet employer needs. IRCs work with SSOs to prepare annual forecasts and business cases to identify emerging skills gaps and project needs to update and maintain the relevance of training products.

• Skills Service Organisations (SSOs) – independent service organisations providing technical, operational and secretariat functions to their IRCs. This includes preparing business cases for change, developing and revising new training packages, and reporting to and liaising with the AISC. Six SSOs support 67 IRCs.

In 2016, the new operating model came into effect. As the transitional period is complete and stakeholders have worked through two planning cycles under the new system, we can now assess the comparative advantages of the new model, and suggest potential lessons for policy-makers facing similar challenges in other jurisdictions.

The new governance model, with defined roles and responsibilities for each entity, is detailed in Figure 1.

Lessons from the AISC reforms

In seeking to determine the impact of the AISC era, the authors asked interview subjects what they viewed as the successes and comparative advantages and disadvantages of the new governance structure, how the AISC was viewed within their professional networks, and to provide anecdotal insight where applicable. The key themes to emerge from these interviews were:

Clearer accountability and standardisation of processes

Respondents agreed that, under the AISC model, stakeholders’ expectations and standard roles and responsibilities of the training package development, endorsement and implementation process was clearer and more process-oriented, as a result of targeted briefings and communications. Clearer role definition improved accountability and responsiveness from the IRCs and SSOs in revising packages. However, final approval for implementation, which requires CISC agreement, remains time-consuming and a potential bottleneck. It was also noted that drafting of training packages for new and emergent industry remains an iterative process slowed by determining scope, identifying and engaging with new stakeholders, and mediating conflicting views.

Development of an economy-wide narrative for skills

All respondents agreed the AISC has been proactive in creating a sense of collective purpose, and generating and disseminating an evidence base to identify and respond proactively to cross-sectoral trends and skills needs. Through initiating a comprehensive annual qualitative survey of IRC members’ skills and insights, the AISC has been able to successfully commence thematic cross-sector projects tackling subjects such as automation, digital skills and disability inclusion.

Greater consultation with industry expert advisers

As of 2019, the AISC has enabled 67 IRCs with a combined membership of approximately 800 stakeholders (compared with 12 Boards and approximately 100 stakeholders engaged under the ISC model). Respondents’ overwhelming view is that more people and newer voices with first-hand knowledge of the skills required by industry are being engaged throughout the process. However, some respondents suggested more effort could be made to engage representatives of small to medium enterprises.

Conclusion

There appears to be general consensus that the adoption of the AISC has been successful in improving consultation with stakeholders and the responsiveness and accountability of the support entities.

The AISC, with its overarching governance and strategy role, has also successfully been able to identify trends and skills needs with cross-sector implications, determine strategic priorities and initiate cross-sector projects to address these challenges in a method which would not be possible under the previous training package development structure.

Literature

Atkinson, G. & Stanwick, J. (2016). Trends in VET: policy and participation. Adelaide: NCVER.

Bowman, K & McKenna, S 2016, The development of Australia’s national training system: a dynamic tension between consistency and flexibility, NCVER, Adelaide

COAG CISC VET Reform – CISC Communique April 2014 [https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/cisc-communique-april-2014]

Department of Education and Training (2014) Review of Training Packages and Accredited Courses – Discussion Paper. Canberra. Commonwealth of Australia.

NCVER (2013), Australian vocational education and training statistics: employers’ use and views of the VET system 2013, NCVER, Adelaide

Noonan, P. (2016). VET funding in Australia: Background, trends and future direction. Melbourne: Mitchell Institute.

About INAP

INAP, the International Network on Innovative Apprenticeship has steadily grown to incorporate researchers from all over the world. In 2019 it’s 8th international conference hosted by Konstanz University, Germany, points to various issues linked to contemporary apprenticeship reforms and reconfigurations, which indicates the need for apprenticeships to deliver on its promise of workplace skills and for it to evolve and also to change as the world economies develop.

Apprenticeship is a model of work and training, which has benefits for many different types of economies and societies. Specific areas of research are represented in Konstanz by the following topics and from different countries’ perspectives:

Governance and Stakeholders

Teaching and Learning

Academisation in Apprenticeships

Diversity and Inclusiveness

Internationalisation and Transfer of VET Services

Future Work: New Employment Patterns

Future Work: Industry 4.0

School to Work Transition and Youth Employment

Modern Fields of TVET Research and Practice